| |

Introduction

Cephalodella forficula (Ehrenberg 1832) is found in a sessile tube which it makes from mucus and detritus and in which its swims back and forth.

A number of Cephalodella forficula rotifers were found in tubes in a small, slightly acid-water pond near Glasgow. All the tubes collected were free-floating, not attached to the leaves or stalks of water plants, and all held rotifers.

Some rotifers without their tubes were placed in cell slides in filtered water from the collecting pond. Others were removed from their tubes and placed in un-filtered water. Further cell slides were loaded with tubes containing rotifers. As a control sample, some rotifers were kept in their tubes as found in the original sampled pond water. In this, the rotifers behaved in the same way as the rotifers listed above. The cultures were placed on a shelf at room temperature.

All these rotifers build new tubes, both in the cell slides holding released rotifers in filtered and unfiltered water and also in the cell slides containing free-floating tubes. The rotifers in the tubes in the control sample also built new tubes, some fixed to weed stalks and some to the wall of the culture dish.

Tube building

After a rotifer hatched, it would generally spend up to two days in the brood tube before leaving it, but rotifers were observed remaining in the brood tubes for up to four days and longer, and at times 3 adults were seen in one tube.

Once a young rotifer (which is smaller and more transparent than its mother) leaves the tube, it can swim very well and appears to feed while doing so. The time from leaving the brood tube until the young rotifer starts to build its own tube appears to be around two days. On two occasions, the mother rotifer was seen to leave the brood tube, build a new tube and lay another egg, while the young rotifer remained in the original brood tube and laid an egg in it.

The tubes can be of various lengths, curved, straight, two touching, glued to the support surface, or free-floating. Even when the tube is of a free-floating type one can observe the rotifer within extending its tube.

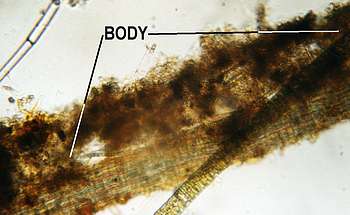

When building a new tube or extending an old tube, the rotifer seems to lay down a sticky cement from glands near the toes. Then, using its head, it pushes detritus onto the support surface. Finally, turning, it spreads its toes wide, forming the tube. The make-up of the tubes can be different, from almost clear to a mass of thick dark detritus. The floating tubes tend to be the ones with a great mass of detritus on their outer surface. The attached tubes appear to remain very clean and clear.

The insides of the tubes seem very stable. Though the rotifer swims up and down the inside of the tube, one does not see any disturbed particles. The rotifer in a tube made on a support surface will put its head or toes out of the tube, but after a time it appears to close one end, extending the tube from the other end.

Tubes which hold a rotifer are very rarely entered, and never by another rotifer. On one occasion a rotifer was observed feeding on protozoans which had entered the tube.

The outsides of the tubes are well grazed by other rotifers, mainly Mytilana sp. and Colupella sp. This was seen in the control sample. When swimming inside the tubes, the rotifer swims with the ventral body-surface down. They also swim in this position when swimming free, but one can see them swimming in the floating tubes on their sides. Could the tube have a bottom and a top when built, which the rotifer recognises even after the tube parts from the leaf or stalk surface it was fixed to?

The rotifer turns at the end of its tube, very like a swimmer turning at the end of a pool. Its travels up and down the tube can be one of stops and starts. The rotifers in the free-floating tube swim the full lengths of their tubes almost non-stop. The tube length does not appear to affect the reproductive rate very much, and eggs were often laid in very short tubes soon after the rotifer started to build it.

The rotifers can be seen feeding inside their tubes. Tubes are typically inhabited by one rotifer. When two or three rotifers are present, they touch their sensory cirri, and both move aside, allowing each other to pass. When the tube contains an egg and the egg is near hatching, when it can block the width of the tube because of its oval shape, the rotifer grips the egg quite hard, flicking the egg to one side so it can pass.

A few tubes were occupied by three adults and two eggs. This was the largest number seen in one tube. Mostly there was only one rotifer and one egg in each tube until the egg hatched, and the offspring remained in the tube with its mother for a little time -- one or two days. One rotifer occupied the same tube for over 12 days. Other tubes which held a rotifer the day before were found empty the next day.

Dodson (1984) records that the tube walls are impregnated with bacteria, and he wondered if these bacteria provide enough nutrition for the rotifer in a closed tube. He gives some interesting facts regarding bacterial productivity. The major kinds of bacteria are a spherical form about one micrometre in diameter and a broad form about 3x 0.5 micrometres.

Reproduction

Dodson recorded seeing only two eggs, neither of which hatched, and the young only born alive. At no time did I see a rotifer young born alive. According to my observations, eggs are laid one at a time, and the time taken for them to hatch seems to be very constant, about five to six days. The eggs are oval in shape, 40 micrometres long by 20 micrometres wide, and increase in size just before hatching. After hatching, the young can remain in the brood tube with their mother and her new egg, plus the offspring's own egg.

Over the whole 38 days that these rotifers were observed within the cultures, the laying and the hatching followed the same sequel to quite a tight timetable. This held true in all the cultures. Only very near the time the egg was about to hatch was any movement seen within the eggs. I was fortunate to see one egg at the point of hatching. Once the hatched rotifer leaves the brood tube, it does not return, but the same rotifer can, after some time swimming free, start to build a new tube close to or touching the old brood tube and soon lays an egg. Other newly hatched rotifers build quite a distance from their brood tube.

In samples from open water, one finds waterweed holding clumps of Cephalodella forficula tubes with rotifers within. In my culture, for reasons of better observation, the individual tubes were singled out. Other cultures were in 50 mm diameter petri dishes, where a number of tubes were cultured together. These were free-floating tubes, and very soon tubes were being built on the base of the dish. Once the rotifers leave the brood tube they are difficult to see until they start to build their tubes.

Most days they were observed two or three times per day, keeping a time log with details of egg laying and hatching and the numbers of eggs and rotifers occupying each tube. The appearance of eggs was very unpredictable.

References

DODSON, Stanley: (1984). Ecology and behaviour of a free-swimming, tube-dwelling rotifer, Cephalodella forficula. Freshwater Biology, 1984, 14, p.329-334

I wish to acknowledge the help of Mr Eric Hollowday, Dr A. Saunders-Davies and my wife, Mrs Sarah Longrigg, in writing this paper.

Fred Longrigg

7 May 2001

| |

|

|